Engineers Week is next week, and I’m preparing for a series of in-person talks I’ll be giving in the next month to both college engineering students and high school students who are considering STEM as a career path.

Two of the most common questions I’m asked are:

From students: “How did you know/decide/figure out which STEM field to go into?”

From college seniors/grad students & young professionals: “How did you find your career passion?”

This is a question I have often posed to mentors myself as I searched for my own career path.

One of the interesting things I’ve noticed is that when I’ve put this question to male engineering mentors, the response is often something to the effect of:

“I loved taking apart and putting back together things as a kid.”

“I loved the puzzle of a car engine.”

“I enjoyed math and science as a kid and engineering seemed a natural fit.”

When I delved deeper, it almost always turned out that those engineers had a parent, teacher, or other adult mentor that exposed them to the wonders of STEM as a young child.

When I’ve asked women mentors that same question, it was rare that a woman would cite mechanical inclinations (i.e. taking apart and putting together things) as the reason she pursued engineering. Instead, I was much more likely to hear the response:

“I was good at math and science in school, and my high school guidance counselor (or parent, or teacher) encouraged me to consider engineering.”

“I learned about engineering in college and fell in love with a class I took on the subject.”

For a long time, I felt envious of those engineers that were inclined towards engineering from childhood. That envy led to me thinking that because I had no interest in doing things like figuring out the inner workings of a car engine, engineering wasn’t going to be the field for me.

In talking with other women, I am far from alone in that experience.

That’s why we need to be very, very careful of the stories we tell students interested in STEM during Engineers Week. There’s a misconception out there that you should focus on your “natural abilities” to find your passion and to choose your field of interest. And while I certainly don’t believe everyone can or should go into STEM, I think we need to openly question where the so-called “natural abilities” originate.

Are those “natural” abilities only “natural” because of an interest that had the appropriate environmental conditions (most often an encouraging role model) to nurture and grow?

As an introvert formerly terrified of speaking in front of a crowd who now comfortably gives speeches, as someone who swore she would never start a company who is now an entrepreneur, as someone who changed majors three times during college, and as an engineer turned author, I think many well-meaning people have the whole “find your passion” thing entirely wrong.

Your current “natural” abilities may have started with an innate interest, but that interest didn’t get you to the strength you consider those abilities now. That took years of work and practice to arrive at some level of mastery.

That’s why I believe passion is not born, it’s built. It’s not something you’ve lost and can find. It’s something you develop over time. Yes, you can “find” the interest (hence all the Engineers’ Week activities), but you don’t typically develop a passion until you’ve demonstrated some level of competency at it. That would be like saying “my passion is painting” when the only form of painting I’ve ever done has been with my own fingers in Kindergarten.

Passion is Built, Not Born

What evidence demonstrates that passions are built instead of born?

Consider that you aren’t born knowing how to engineer complex systems out of the womb. Einstein’s first words were not E=mc^2. In fact, despite studying diligently in preparation for the entrance exams to college (in his case, Zurich Polytechnic), he failed them the first time and spent the next year in a different school preparing to retake the examination, which he passed the second time.

Research on child prodigies shows that while many studies indicate they have higher-than-average IQ, they also very often had parents who enabled and pushed them to practice their craft from a very young age. Mozart, for example, started playing music at the age of 4 and was composing at 5. His father was a highly sought-after music teacher. More recently, the tennis starts Serena and Venus Williams were moved as children from California to Florida so they could be taught at an elite tennis academy.

Ask any elementary school teacher, and they will tell you that the children that usually learn to read the fastest are almost always the ones whose parents emphasize and encourage reading at home. The same trend is observed in exposure to math and science. Kids of engineers and scientists are, statistically speaking, more likely than average to become engineers and scientists. That effect is even greater for women specifically, according to https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3068971 this study, a collaboration by the University of Michigan and University of Arkansas.

Anecdotally, I’ve seen this in my own kids. For example, we signed our kids up for the church choir starting in Kindergarten, where they perform for the entire church once a month. The early years were rough, as the kids did not want to start in front of everyone to perform. Yet, as their proficiency grew, so did their enjoyment of the activity. This year, my oldest daughter had her first choir “try-out” at school, where 3 kids were selected from the entire 5th grade to participate in a signing festival. She made it, and interestingly enough the two other kids that we also selected had also been in some sort of choir/performance group from a much younger age than the average student in their class.

This tells us that passion and proficiency are linked.

Last month I had the privilege of hearing Tom Bilyeu, millionaire co-founder of Quest Nutrition (that he’s sense sold) and Founder of Impact Theory, speak at a conference. He shared the story of how, as a young adult, he was lazy, fat, and rudderless. Tom said, “My own mother assumed I wouldn’t go far in life.”

Tom further shared that he was initially unable to get permission from his current father-in-law to marry his now wife, because he had no job and no ambitions. Tom states that at the time, his now father-in-law was right. There was nothing in Tom’s background that would have indicated he had the capacity to become a millionaire. He was not a “born” entrepreneur. It was only when he began applying himself to his craft that he found his own passion. (You can read more about Tom’s story HERE if interested.)

That passion – and the skills needed to pursue those passions - is built is great news for everyone. Progressive growth is how you build career passions and strengths. A drive for growth will beat raw talent that’s become complacent every day of the week.

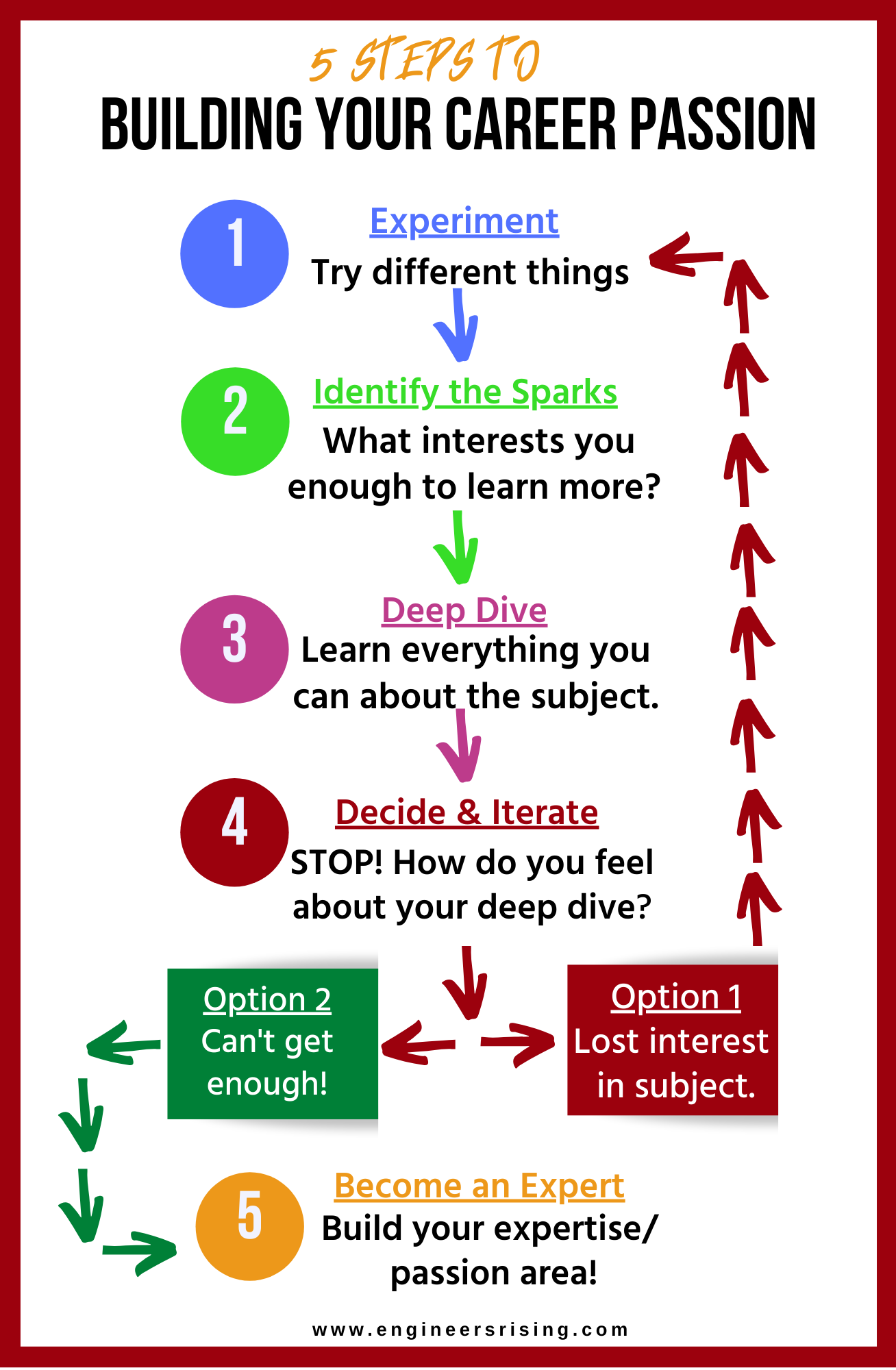

In this blog I’m going to share a 4 step framework I initially learned from Tom’s work a few years ago, and have adapted to my own experiences and the experiences of other engineers. Use it to build (NOT find) your own career passions.

Like what you’re reading? Join our movement, and get exclusive tips and tools curated for women in engineering.

Five (Iterative) Steps to Finding Your Career Passion

1. EXPERIMENT

The first step to finding your career passion is to experiment. Ask yourself these questions:

What things in your field you enjoy?

What career paths spark your interest?

Who in your field is doing what you want to do down the road, and how did they get there?

What does that look like in practice? For some, it can mean job-hopping, but it doesn’t have to. Working at a large, diverse company with many different divisions of engineering can have the same effect, so long as you are willing/able to transfer departments. Working at a small company where you are forced to wear many different hats can also be beneficial.

I can’t overemphasize the importance of being willing to experiment with your career roles. For most engineers, staying in one role or firm too long (except in the case of being able to switch roles within a large organization) is detrimental to building your passions and career expertise in the long-term. Most of us don’t find the thing that really sparks our interest right out of the gate, in our very first job. It takes a bit of trial and error to find those areas of interest.

Additionally, working with someone who wants to help you grow (as opposed to simply fulfilling an assigned role) can truly fast-track the experimentation process. Remember, the common thread in both the child prodigies and in my mentors who found their passions is that someone helped that interest bloom. That is the effect and importance of finding good mentors.

For me, experimenting meant changing college majors several times, trying large and small companies, and volunteering to work on different types of projects until I found the right fit for me. It meant trying some things that weren’t directly related to my job, like running for an elected board position in a non-profit, running a tennis tournament, and writing a book. This will look different for everyone, but the process is similar for all.

You have to try new things. Some will spark your interest (and if they do, go straight to step 2). Others will leave you apathetic or with the thought “I never want to do that again.”

When I was in a work “rut”, lack of experimentation (and the growth that accompanies it) was always a primary reason. If that’s you, the fastest way out of that rut is to try something new as soon as possible. Here’s a couple of ways you can take a small step towards more experimentation:

Apply/interview for a new job

Take a peer out to lunch who loves what they do

Be a short-term volunteer in an area that you have an interest, but lack experience (examples: Engineers’ Week activities, Habitat for Humanity build, Engineers Without Borders project volunteer)

Mentor or be mentored by someone

Physically challenge yourself (i.e. Train to run a 5K)

Grow your own voice: Try attending a Toastmasters’ meeting, research and write a short LinkedIn article about a topic of interest, or start a YouTube Channel

Enroll in an online personal or professional development course of interest.

2. IDENTIFY THE SPARKS

Identify those things that spark your interest. What things, when you hear about them, do you have the instant thought “I want to learn more about that!” If you’ve identified one or more things, move to step 3. Otherwise, go back to step 1 and continue to experiment.

3. DEEP DIVE

Once you identify the areas that spark your interest, it’s time to do a deeper dive into the subject and engage with those areas of interest. Learn everything you can about it. Geek out on the topic. Go down that rabbit hole. Here’s a list of multiple ways you could learn more:

Request to work on a project of that type (best way!)

Internet research

Read books

Interview expert mentors in that area

Listen to podcasts on the subject

Attend sessions on the topic at a conference

After you’ve taken some time to really get into that area, it’s time to decide if you will continue down this path. Move to step 4.

4. DECIDE & ITERATE

One of two things will happen when you do a deep dive into an area of interest.

Option 1: You lose interest, get bored, or decide this subject is not for you. If that’s you, go back to step 1.

I want to dwell on this one a moment, because many of the engineers I’ve coached get to this step, decide that they already have “expertise” in this area, and stay here even though they’ve lost interest. One or more years later, they are frustrated that their career has stagnated and they feel unfulfilled and miserable.

Repeat after me: your career only grows as much as you do. If you stop growing and learning, your career options will be limited. If you are growing and learning in an area you don’t enjoy, you are headed towards bitterness and burnout.

Option 2: Your deep dive leads to a fascination with the topic.

The more you learn about a topic, the more interested in the topic you become and the more you want to learn. If this is you, it’s time to move to the final step.

5. TURN FASCINATION INTO EXPERTISE

Now, it’s time to dive in and become an expert in your particular niche! This is where the subject matter experts in your industry reside. It is where your fascination leads you down the path of mastery. You can’t enough of this subject. Your fascination leads you to continue to learn everything you can, engage deeply with the subject, and seek out other experts, mentors, and peers you can learn from.

THIS is your passion, an area of expertise unique to you that you have both competencies and market value.

Build Your Career Passions

Building your career passions is not a fast or easy process. It truly is a long game that creates a cycle of momentum. The more you engage in an area of fascination, the more you want to learn and the more expertise you develop. The more you learn and the more excited you become about a subject, the more other people want to learn from you because your energy for the subject is contagious!

For me, this process has played out in everything from my college major selection to my current business. In college, I started out as a biochemistry major. I busted my tail to get a C in my first college chemistry class, and then I worked in a lab for a summer when I discovered lab work was not interesting to me. That sent me back to step 1. Next, I took a programming course. It’s the only class I’ve ever fallen asleep in. That also sent me back to step 1. Finally, I accidentally stumbled onto my college major when I met a friend to play tennis, who had come straight from class with an architectural model in hand. I wanted to know what engineering class had you both doing engineering AND making architectural models. The answer to that question: “architectural engineering.” I took my first class in that major and feel in love with the topic, going on to have a successful 15 year career in that area.

Writing She Engineers came about in a similar way, for both the writing itself and the topic of the book. I became completely fascinated with the subject of women in leadership when I read Lean In for the first time. I wondered how exactly that applied in engineering, and did a deep dive into the research available to learn all I could. The more I learned, the more I wanted to learn. The more I learned, the more I tested it on myself and shared it with others. The more I tested it and shared it, the more obsessed I became and the more knowledge I acquired. That has lead me down the (in-progress) path towards subject mastery.

Like what you’re reading? Join our movement, and get exclusive tips and tools curated for women in engineering.

I believe that the only people who will create change in the world, who will really make in a difference in the lives of others, and who will reach their highest potential, are the ones who actively seek out their own career passions. These are the innovators, the visionaries, and the leaders.

Others develop expertise in an area that they are not really interested in due to some sort of fear (fear of failure, what others think, financial security, etc.). They get to step #4, ignore/suppress their own feelings about a subject they are not really interested in, and focus solely on where they’ve already developed experience as the path forward, creating a cycle of apathy at best. We all know more than one of those people, who have stayed here for years: passionless and cynical, they are simply going through the motions of their jobs and can’t wait to retire.

Behavior that is driven by fear will NEVER result in the extraordinary, limitless career of which you are capable.

Building your passion requires courage. It requires you to uncover abilities that you may not currently know that you have.

And here is where it gets scary, especially for women in STEM. Consider what will happen if your passions are NEVER built because they happen to occur in a physical body and mind that doesn’t conform to gender stereotypes. What happens if we allow lack of confidence, fear of failure, gender bias, and fear of what others might think of us to keep us on a path where we have “experience” but no (or declining) interest? What innovations will be lost because we were afraid to focus on and build our passions? What in our own potentials is lost because we were afraid to take a leap towards our own unique passions?

Be the engineer who doesn’t settle for ordinary. Build your own unique passions, and open yourself up to a world of limitless possibilities.

Where are you in the process of building your career passions? Comment below!